Nancy Maple had spent mere minutes in the Crimson Lodge before I got her killed in The Crimson Diamond. The amateur mineralogist — on an errand with the Royal Canadian Museum, where she works as a clerk — spent hours on a train heading deep into the Canadian wilderness, in search of diamonds. I figured she’d like a shower. So I click Nancy through the Crimson Lodge, peering into rooms and occasionally saying hi to other guests. I find a bathroom with a tub and shower, maneuver Nancy next to it, and type Take a shower. It doesn’t work, because Nancy is fully clothed. I type Undress, and Nancy won’t do it because the door’s open. Makes sense! I point Nancy to the door. Close the door. Now Undress. Back at the shower, I peck out Turn on water valve on my keyboard. Switch to shower. Now Nancy can get in.

But then, The Crimson Diamond cuts to a different angle, Nancy’s silhouette behind a shower curtain. The music shifts. Anyone who’s seen a horror movie knows what’s about to happen next — the door handle jiggles. The door opens. Nancy is stabbed to death. I forgot to lock the door.

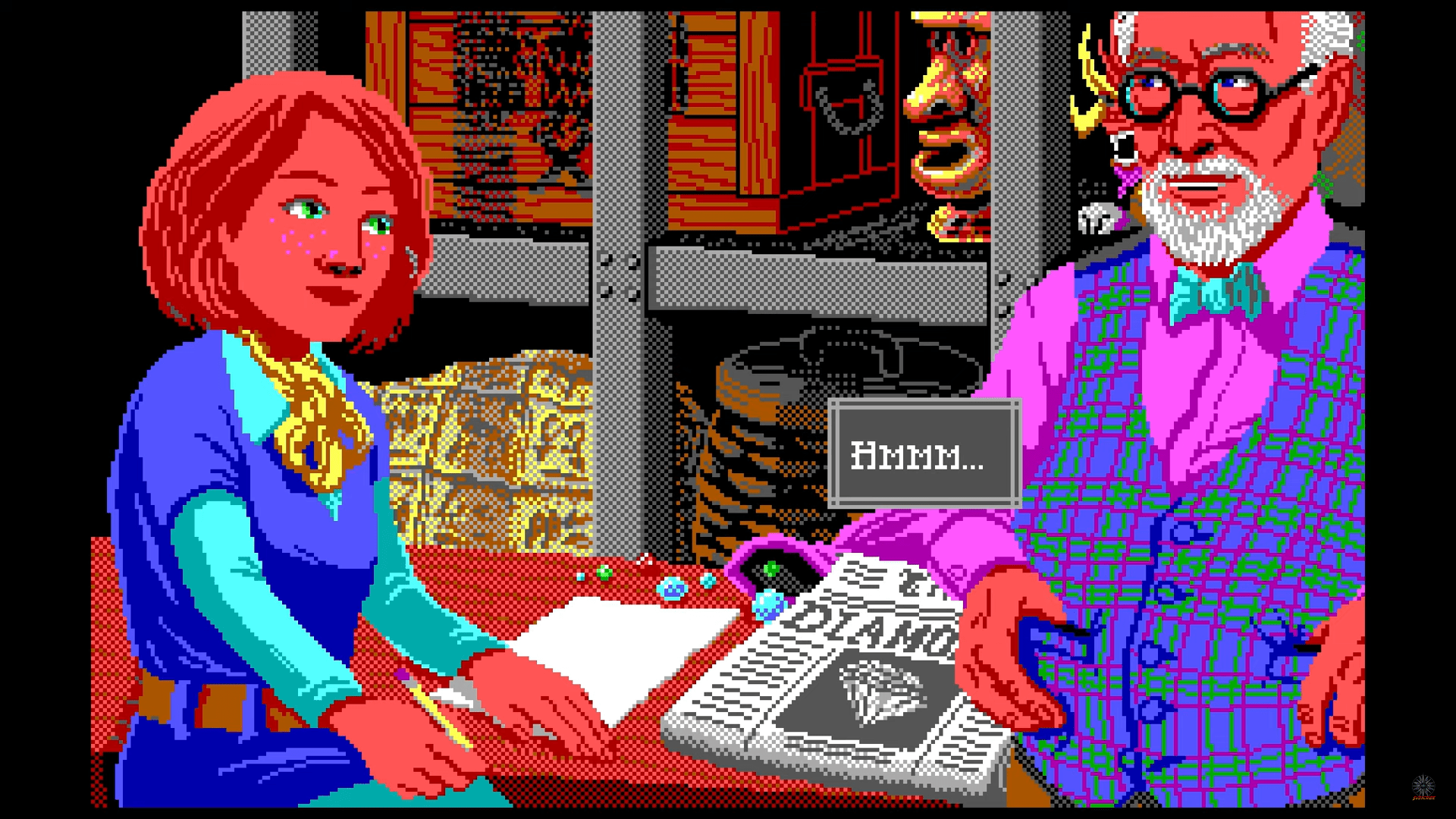

The Crimson Diamond, from developer and illustrator Julia Minamata, is a game about precision. Not precision in terms of movement, but precision with words. Minamata’s first solo-developed game uses a text parser to control the action. (Except Nancy herself; she moves with a mouse click or arrow buttons.) It’s a feature that was commonly used in games from the the ’80s and early ’90s; Sierra On-Line is known for its text parser games like King’s Quest and The Colonel’s Bequest: A Laura Bow Mystery. Instead of pointing and clicking in these games, you’re typing out commands. If you want Nancy to eat a rock, you type Eat rock. (She might not do it, though.)

“You don’t see a lot of text parser games nowadays,” Minamata told Polygon. “I’m not going to say I’m surprised by it, but at the same time, we’re a society where we’re texting and typing all the time. It’s this constant thing. We’re interacting with each other and the written word all the time. I just love this way of interacting with a game. It feels like there’s unlimited possibilities.”

This is where being precise with language comes in. Even the smallest tweak of a word will change what happens. You can look around a room, but what if you examine something? And, again, as I learned, what if you close the door, but don’t lock it? Nancy’s almost immediate murder — which, in turn, had me start over at my last save — was the perfect lesson I needed to understand The Crimson Diamond and what it was asking of me.

The game begins with Nancy Maple hopping on a train into a remote lodge in Ontario, where she’s to investigate a mysterious diamond that was sliced out of a fish’s belly. Diamonds aren’t common in the area, or so they say, and so a couple others are flocking to the area, too: Family members of the Lodge owners looking to claim an inheritance, a curious Japanese Canadian birdwatcher (a tribute to Minamata’s family’s history in Canada, she said), and a government geologist. Everyone expects it to be a quick trip, but a bridge explosion suddenly strands them all at the lodge with its grumpy owner, house staff, and the owner’s wife. Chaos ensues — both around the family drama, a failed mining town’s history, a death (not Nancy’s!), and, of course, the diamond.

The Crimson Diamond is divided into seven different chapters, most of which take place in the Crimson Lodge and its surrounding grounds. Over the course of several hours, you’ll get very familiar with the characters and their stories, both as individuals and with regard to how their backstories play into the larger mystery. Nancy becomes the de facto detective who pieces it all together. One of the early mysteries is a robbery: Someone’s stolen an expensive brooch and a couple of steins. It’s Nancy’s first foray into detective work; to do it, you’ve got to find makeshift tools to dust and examine fingerprints before finding the culprit. You’ve got to get fingerprints for everyone in the house, some of which are as simple as just asking, but others require more thinking and foresight, like feeding a man a cookie so salty that he’ll need a drink — an action that requires him to touch a glass from which you can later lift a fingerprint.

The game quickly becomes more complex and layered, but Minamata said she didn’t want The Crimson Diamond to be punishing, like early text parsers could be. (If you get stuck, Minamata put a full hint guide online; there’s no way to simply get stuck so badly you’ll have to stop playing.) The parser itself is a little more forgiving with words, for instance. You can’t accidentally progress the game in a way that has you missing important clues. It doesn’t have the easy, sudden deaths of The Colonel’s Bequest, either. “That’s something you have to work for,” Minamata said. “My kind of puzzle is the idea of something so straightforward that you would think to do in real life that, for some reason, just slips our mind when playing a game. But if you do it, you get rewarded by, Hey, you survived the shower this time.”

These tweaks don’t make The Crimson Diamond easy, by any means, but they do lessen frustration, allowing you to really dig in and enjoy the world — not fear it.

The Crimson Diamond was released Aug. 15 on Mac and Windows PC. The game was reviewed on Windows PC using a pre-release download code provided by Julia Minamata. Vox Media has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content, though Vox Media may earn commissions for products purchased via affiliate links. You can find additional information about Polygon’s ethics policy here.

Source:https://www.polygon.com/impressions/446232/crimson-diamond-julia-minamata-text-parser-review-impressions-interview