“Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic book industry. They get the children much younger.” So declared renowned psychiatrist Dr. Fredric Wertham on April 21, 1954, the opening day of hearings before the U.S. Senate Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency.

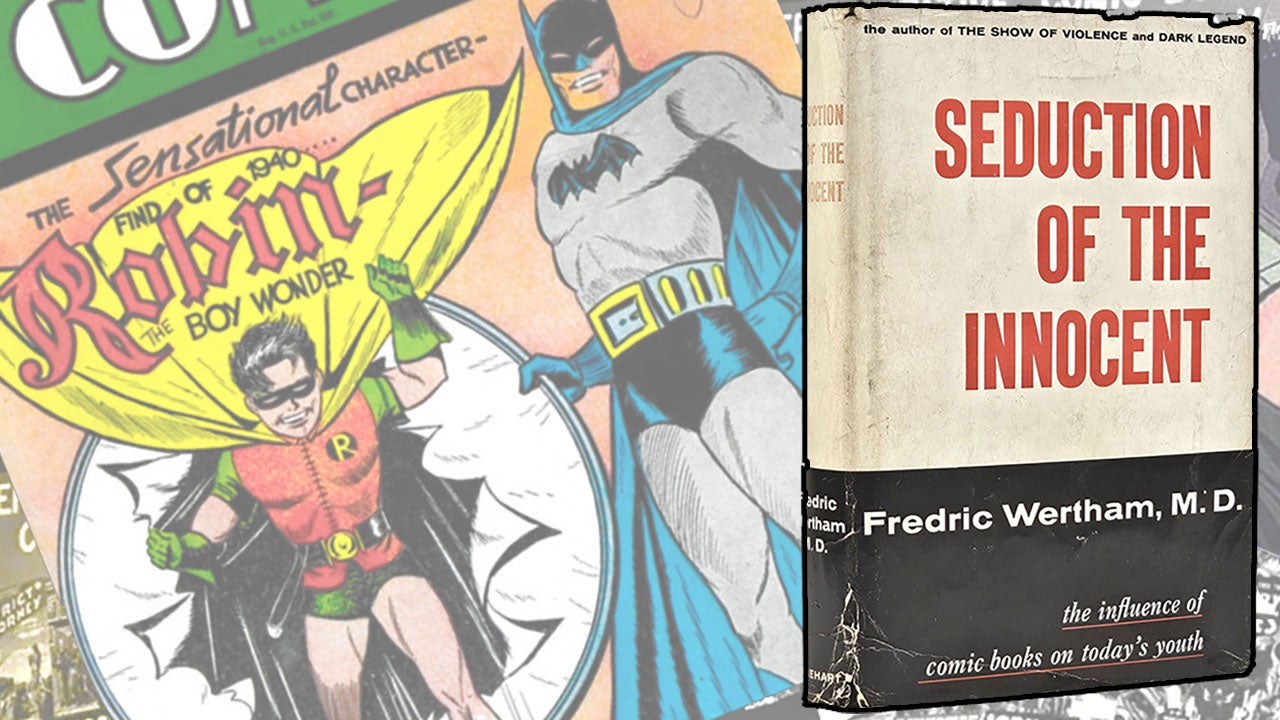

Wertham’s own book, Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth, had just come out two days before, the culmination of his six-year public crusade against comics.

The book and Senate hearings sparked a national panic about comic books that nearly decimated the industry, with lasting consequences to this day.

The Halcyon Days

With World War II over, superheroes fizzled. The popularity they enjoyed fighting for Uncle Sam became awkward jingoism, and they became champions without a cause. Other genres of comics flourished in their stead, like comedy, science fiction, detective mysteries, Westerns, romance and horror.

Together, these genres made the comic book medium more popular than ever. In 1944, an estimated 18 million comics sold on newsstands every month. By 1949, it was 60 million. In his book, The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America, David Hajdu writes that “the comic book was the most popular form of entertainment in America… reaching more people than movies, television, radio, or magazines for adults.”

Every third periodical sold in the U.S. was a comic book. By 1952, more than 20 publishers were producing nearly 650 titles a month.

The Rise of Horror Comics

EC Comics, standing for “Educational Comics,” was founded in 1944 by Max Gaines—the man who invented the comic book—to publish series like Picture Stories From the Bible, marketed at schools and churches. When his son Bill inherited the company in 1950, Bill changed the name to mean “Entertaining Comics” and began publishing series like The Haunt of Fear, The Vault of Horror, The Crypt of Terror (later Tales from the Crypt) and Weird Science.

Horror comics had been around almost as long as superheroes, but EC’s series became a hit. Partly because, aside from gore, they contained some of the best art and storytelling in comics. Other publishers jumped on the bandwagon, with titles like Horror From the Tomb, Adventures Into Terror, Journey Into Mystery (which years later would introduce and be retitled Thor), Weird Fantasy, and many others.

By the end of 1952, about 200 monthly titles were horror—nearly one in three comics. Though many were just macabre cautionary tales, many others featured gruesome violence and salaciousness, aiming for shock value. The epitome was the cover of EC’s Crime SuspenStories #22 (May 1954): A man with a bloody axe holds up his wife’s severed head, her eyes rolled back and blood dripping out of her mouth.

Attack of the Mad Scientist

Criticism of comics was also nothing new. As far back as 1846, famed British poet William Wordsworth lamented in his poem, Illustrated Books and Newspapers, how “prose and verse sunk into disrepute” by being combined with “dumb art.”

A century later, in May 1940, Sterling North, Literary Editor of the Chicago Daily News, wrote an op-ed titled A National Disgrace and a Challenge to American Patents, in which he claimed comics were “a strain on young eyes and young nervous systems—the effect of these pulp-paper nightmares is that of a violent stimulant.”

But this type of tongue-clucking was mostly ignored. Until the right man showed up at the right time to convince the American public of the horrible dangers lurking in the pages of comic books.

Dr. Fredric Wertham was a highly distinguished psychiatrist specializing in forensic psychiatry. Among other things, he was director of mental health services at Bellevue Hospital and head of the psychiatric clinic of the Court of General Sessions (later renamed the State Supreme Court).

He was also a social crusader of true conviction. In Baltimore, he treated Black patients when no other psychiatrist would. In 1946, he founded the Lafargue Clinic in Harlem, possibly the first in the U.S. to provide low-cost mental health care, mostly to people of color. A champion of desegregation, his testimony was important, perhaps instrumental, in the 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education.

But Wertham was also a prig who fancied himself a cultural critic. He disliked anything born of mass culture, including film and television, and his strongest disdain was for comic books.

In March 1948, Wertham began his crusade against comics with an interview in Collier’s titled Horror in the Nursery, where he first put forth his theory: Many of his patients were considered juvenile delinquents, and since almost all read comics, clearly “comic books are an important factor in juvenile crime.” He followed with other articles.

With impeccable credentials, Wertham rode the wave of American postwar paranoia about juvenile delinquency. In 1954 he published his infamous book, Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth.

Dr. Fredric Wertham’s Bad Book

The overarching argument of the book is that comics aren’t just a catalyst for delinquency, but a root cause. They brainwash otherwise well-adjusted or mildly susceptible youths into perverts and murderers.

“Comic books are an invitation to illiteracy, create an atmosphere of cruelty and deceit, stimulate unwholesome fantasies [and] suggest criminal or sexually abnormal ideas,” the book starts off. They cause “a blunting of… conscience, of mercy, of sympathy… [and of the] taste for the finer influences of education, for art, for literature, and for the decent and constructive relationship between human beings.”

The worst are “crime comic books,” which are classified as anything depicting a crime. The worst of the worst are superheroes, “a special form of crime comics.”

The “phallic” Wonder Woman “tortures men,” is a “frightening figure for boys” and “an undesirable ideal for girls, being the exact opposite of what girls are supposed to want to be” (meaning demure).

“Batman stories are psychologically homosexual,” the book asserts. Conflating homosexuality with pedophilia (a common phenomenon in those days), it claims they “fixate homoerotic tendencies by suggesting the form of an adolescent-with-adult… type of love-relationship.” The proof? Bruce Wayne’s ward is named “Dick,” whom he shares “an idyllic life” with in “sumptuous quarters, with beautiful flowers in large vases.”

As for Superman, he “undermines the authority and the dignity of the ordinary man and woman in the minds of children” and “gives boys and girls the feeling that ruthless go-getting based on physical strength… is the desirable way to behave.” Superman’s iconic costume is really “a mixture of the costumes of S.S. men, divers and robots,” Wertham writes. “The big S… we should, I suppose, be thankful… is not an S.S.” Superman, according to Wertham, is a Nazi.

Dr. Susan Hatters-Friedman, director of Forensic Psychiatry at UH Cleveland Medical Center, has coauthored two articles on Wertham for scientific journals. “The idea that comics were harmful to children and of hidden psychological issues in Superman comics is met with laughter these days,” she told IGN. “But it was a very real concern in the 1950s.”

But Did He Have a Point?

To be fair, Wertham did make some valid points. The content of comics, even superhero comics, isn’t above scrutiny.

Many comics were indeed inappropriate for young readers, and were in fact intended for teens or adults. But without a rating system like today’s MPAA in film (G to NC-17), they were accessible to kids on any newsstand or spin rack. The strong association between exposure to violence in the media and perpetration of violence, particularly among children, has been firmly established, though still largely ignored. Wertham wasn’t wrong or alone in pointing to this.

That said, Seduction is rife with facile arguments. The first among them is that, since almost all the youths Wertham treated read comic books, comics were clearly the main cause of juvenile delinquency. He could have equally blamed air. And by his definition of “crime comics”—any depiction of crime or violence—the Bible, Homer, Shakespeare or Twain wouldn’t have passed muster.

“Dr. Frederic Wertham was an idiot,” author Michael Chabon writes in The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay. “It was obvious that Batman was not intended, consciously or unconsciously, to play Robin’s corrupter: he was meant to stand in for his father, and by extension for the absent, indifferent, vanishing fathers of the comic-book-reading boys of America.”

Superheroes aren’t fascist (an argument that’s still around today). They carry a message not of power over others, but of personal empowerment. They use their gifts not to establish dominion, but to protect the freedom and security of others. Superman isn’t the Übermensch; he’s the antithesis.

Wertham failed to grasp what every child knows. Superheroes are the good guys.

The Witch Hunts

Seduction of the Innocent was immensely influential. It was named Book of the Year by the National Education Association, and Wertham was invited to speak in important forums across the country.

Wertham’s six-year campaign was successful in creating a national scare, which eventually led to the creation of the Senate Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency of the Committee on the Judiciary. Hearings opened on April 21, 1954, coinciding with the book’s release.

It was the height of McCarthyism, and the hearings, led by Senator Estes Kefauver (D-TN), were front page news, televised and broadcast on the radio around the country. Wertham understood these were show trials, and he played his part when as an expert witness he compared comic book creators to Hitler—not even a decade since the war and the Holocaust.

Not everyone agreed. A colleague of Wertham’s, Dr. Lauretta Bender, head of the Bellevue children’s psychiatric service, extoled the virtues of Superman as an inexpensive form of therapy, calling it “mental catharsis.” Dr. William Moulton Marston, Columbia University professor of psychology and co-inventor of the early polygraph—as well as of Wonder Woman—explained that “the wish to be super-strong is a healthy wish… The more the Superman-Wonder Woman picture stories build up this inner compulsion… to battle and overcome obstacles… the better chance your child has for self-advancement in the world.”

The Subcommittee’s own legal counsel noted that Wertham represented the extreme position among psychiatrists, and that in fact most found no meaningful correlation between comics and delinquency. Its report, released on March 14, 1955, concluded; “it appears to be the consensus of the experts that comic-book reading is not the cause of emotional maladjustment on children.” In fact, “the child with difficulties may find in comic books representations of the kinds of problems with which he is dealing, and that comic books will, therefore, have a value for him.”

Comics’ exoneration received little media attention. And the damage was already done.

The National PTA and other groups called for boycotts of comic books, supported by public figures. More than a hundred acts of legislation were introduced across the U.S. to restrict or outlaw the sale of comics. In Canada, selling comics depicting crime was officially illegal until 2017.

Mob hysteria reached its peak when parents, schools, churches and scout troops burned comic books in public bonfires. The same Americans who’d just fought and sacrificed to stop the book burners of Berlin were doing the same thing in their own backyards.

The Creation of the Comics Code

The comic book industry was all but decimated. There were other factors involved, like suburbanization and television, but this was a purge. Sales plummeted by over 70%. When Eisenhower took office in 1953, there were some 50 comic book publishers. By the time he left in 1961, there were 15. More than 800 people lost their livelihood. The Ten-Cent Plague ends with a haunting, 15-page “black list” of publishers, editors, writers, artists and others whose careers and sometimes lives were destroyed. A poignant lesson in the danger of self-righteousness.

To save itself, the beleaguered industry established the Comics Code Authority (CCA), a self-censoring body that imposed the strictest regulations of any media. Diktats included no depiction of zombies, vampires, ghouls or werewolves; dressing all characters “appropriately”; emphasizing the sanctity of marriage; and fostering respect for parents and the government. Every comic that wished to carry the CCA’s seal of approval on the cover had to abide by them.

The code was revised in 1971, but it remained in place for 57 years, before quietly disappearing in 2011. It effectively lobotomized comics, making them inoffensive to the point of insipid.

“It instilled that belief in the American public that comics are strictly a kid’s medium,” Joe Quesada, former editor-in-chief and chief creative officer of Marvel Entertainment, said. “We’re still fighting against that stigma today.”

Legacy: Noble Intent, Huckster or Demagogue?

Historians vary in their treatment of Wertham. Some are more forgiving, believing his intentions were noble and pointing to his impressive record. Others are more ambivalent. Others yet see him as a zealot and a publicity hound. As far as Stan Lee was concerned, “he was a good huckster, got a lot of publicity, and it almost destroyed the comic book business.”

When Wertham’s research archives for Seduction were made public in 2010, Carol Tilley, professor of library and information science at the University of Illinois, reviewed them. She found “numerous falsifications and distortions,” through which Wertham systematically “manipulated, overstated, compromised, and fabricated evidence.” He “edited and altered children’s statements and clinical presentations” and in some cases it seems even created evidence out of whole cloth.

“Wertham seemed to confuse causation with correlation, and other basic issues in research,” Dr. Hatters-Friedman told IGN. “No one seemed to carefully question his ‘scientific methods.’”

Whether Wertham’s motivations were sincere or not, his crusade against comics was sanctimonious and willfully misguided. As a man of science, versed in methodical examination and critical analysis, he knew better. He wasn’t sloppy: His consistent use of omissions, distortions and fabrications could only have been deliberate.

It was demagoguery disguised as progressiveness in service of an agenda, for which he’ll forever remain maligned as the man who almost killed comics.

But, like a proper ghoul, EC Comics will be rising from the grave this summer. As detailed in IGN’s exclusive reveal, Oni has become the official home of the EC brand, producing all-new tales of horror by A-list talent like Jason Aaron, Brian Azzarello, Stephanie Phillips, Lee Bermejo, J.H. Williams III and Dustin Weaver.

Because in comics, no one really stays dead.

Roy Schwartz is a pop culture historian and critic. His work has appeared in CNN.com, New York Daily News, The Forward, Literary Hub, and Philosophy Now, among others. His latest book is the Diagram Prize-winning Is Superman Circumcised? The Complete Jewish History of the World’s Greatest Hero. Follow him on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook @RealRoySchwartz and at royschwartz.com.