The relatively niche subgenre of Black vampire films was popularized by Blacula in 1972, and to date only has a handful of entries — all of which are much less well known among the general public. To celebrate the release of Ryan Coogler’s new box-office hit Sinners, as well as to see what it adds to this particular collection of monster movies, we’ll run through some lesser-known vampire films that feature Black leads (be they hero or bloodsucker) and highlight how the vampire is framed through the lens of Black identity and relevant social issues such as racism and gentrification.

But before we get to the rundown, there are two honorable mentions that won’t be discussed in length due to their prominence in popular culture. The first, the aforementioned Blacula, is noteworthy for being a Blaxploitation spin on the tale of Dracula, who in this version turns African prince Mamuwalde into the titular character after the Prince of Darkness refuses to help him suppress the slave trade. It added a tragedy and an ethos to the vampire tale alongside a healthy dose of racial politics. While this would spawn a sequel with Scream Blacula Scream, this entry is notable for kickstarting a wave of Blaxploitation horror films while also making its titular character a household name. The second, Blade, needs no introduction. Its reverence for Hong Kong action combined with an inherent Blackness and coolness radiated by Wesley Snipes in every frame have made it into a certified classic. The movie has also become part of an annual celebration on social media due to its incredibly iconic opening sequence and introduction to its titular character.

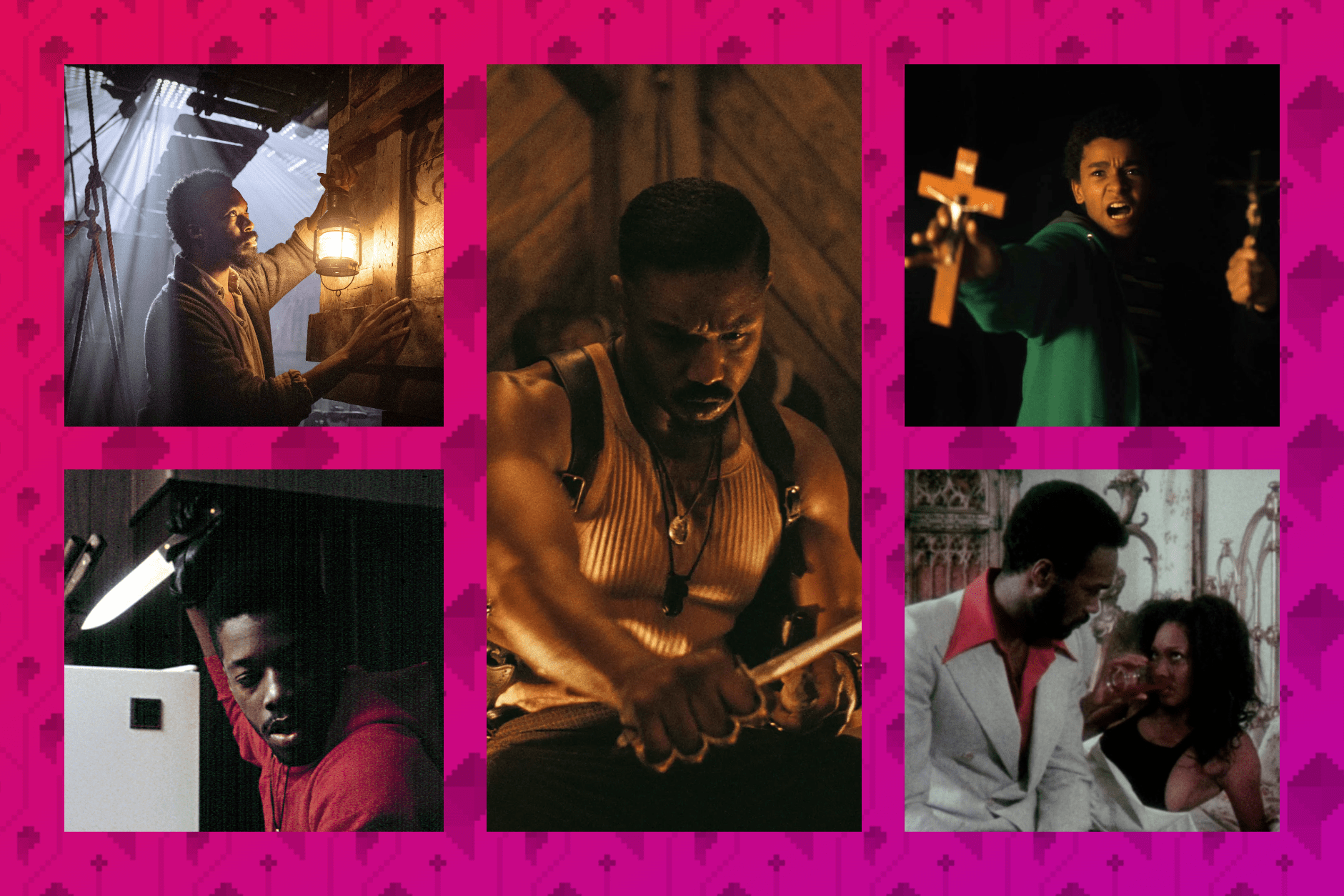

Here are five critical entries in the Black vampire movie canon and how their tackling of social issues adds to the subgenre.

Ganja & Hess

Where to watch: For free with a library card on Kanopy and Hoopla, or for digital rental/purchase on Amazon

Bill Gunn’s underdiscussed sophomore effort was initially retooled and recut upon release due to its poor box-office performance and executive dissatisfaction with its tone and style (despite raving critical reception at Cannes). Unlike the typical understanding of how vampires are made, Gunn’s film depicts their creation through a violent stabbing with an ancient African dagger, which leaves its victims with an immediate desire for blood. The two leads, Dr. Hess Green (Duane Jones of Night of the Living Dead fame) and Ganja Meda (Marlene Clark), soon find their paths crossing as they navigate obstacles as Black people operating within white bourgeois society, as well as their new blood addiction.

Dr. Hess is a wealthy Black anthropologist who, after a violent encounter with George Meda (Gunn), is transformed into a vampire. Hess is eventually joined by Ganja, Meda’s ex-wife, and the two fall both in love and under the influence of their vampiric addiction. Off the rip, the film is presented in a hazy, hypnotic style through its editing that forgoes a conventional linear narrative structure for something much more evocative, erotic, and thought provoking. Flashbacks come in and out of order, with stretches of the film itself seemingly suggesting that a much larger duration of time is passing than what we ourselves are watching. The film is patient for its 110-minute run time, and it deserves to be savored as its two leads come in and out of each other’s lives.

The presentation of these euphoric elements offers a fascinating duology of themes to explore between the two leads. For Hess, the film touches on the idea of an affluent Black male rising to white approximations of privilege, yet still finding himself in a different kind of prison that is an ever-present loneliness. For Ganja, despite the monstrous and “otherly” nature that vampirism represents, there is the suggestion that embracing long-forgotten cultural customs is the key to a life free from traditional societal trappings, be it race, gender, or both. Gunn’s phantasmagoric picture is one that has much to say on the ideas of addiction and cultural assimilation in the face of white supremacy. Although it has faced decades of neglect, the film — in its original form — has since gone on to be reevaluated and heralded as a cult classic of Black horror cinema.

Def by Temptation

Where to watch: Prime Video, Peacock, Shudder, for free with a library card on Kanopy, for free with ads on Pluto TV

After Ganja & Hess, the next Black vampire film would not appear for over a decade — 1986’s Vamp, starring Grace Jones (streaming on Shudder, or for free with ads on Pluto TV). Four years after that, James Bond III’s sole directorial effort, Def by Temptation, would make its mark as an often-forgotten cult classic of Blaxploitation horror. At first glance, this doesn’t technically fit within the purview of a Black vampire film, because its central monster isn’t a vampire but rather a succubus called Temptress. However, she is a vampire in everything but name: She devours her victims, occasionally turns them into creatures like her, doesn’t have a reflection in the mirror, and can only be killed by the power of the cross.

Where to stream the other Black vampire movies mentioned in this piece

- Blacula: Prime Video, or for free with ads on Pluto TV

- Scream Blacula Scream: Prime Video, or for free with ads on Pluto TV

- Vamp: Shudder, or for free with ads on Pluto TV

- Bones: For digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TV, and Fandango at Home

- Vampire in Brooklyn: Paramount Plus, or for free with ads on Pluto TV

- Queen of the Damned: For free with a library card on Hoopla

- Da Sweet Blood of Jesus: For free with a library card on Hoopla

- Black as Night: Prime Video

- Day Shift: Netflix

- The Invitation (2022): Hulu

Much like Ganja & Hess, Bond’s film is indebted to the Blaxploitation films that came before it. With its exaggerated atmosphere and characters, its setting in an isolated and impoverished neighborhood of New York City, and its splattery orange-red blood, the film oozes color and vibrancy in every frame. It even comes with poignant political commentary that touches on aspects of the AIDS epidemic that ravaged poorer communities in the 1980s, as well as the relationship between Black communities and Christianity in both rural and urban environments.

The film follows Joel (James Bond III), a young man raised by his religious grandmother in the shadow of his long-deceased preacher father (Samuel L. Jackson). Disillusioned with religion, he goes to New York City to meet childhood friend K (Kadeem Hardison) and get a taste of the city life. This journey puts him in the crosshairs of the Temptress, who at this point has already claimed multiple victims she has had sex with: a philandering bartender, a married man who she gives a disease to (culminating in his off-screen murder by his wife), and finally a closeted gay man struggling with his own internalized homophobia. Her goal with Joel is to finalize his corruption within the city by tempting him with sex, thus not only killing him, but also destroying the purity of spirit needed to pursue the preacher life he is on the run from.

It’s easy to argue that the film posits a socially conservative worldview that suggests sex outside of heterosexual marriage is a transgression punishable by death. However, given the film’s distribution by Troma Entertainment, known for pushing the boundaries of taste with its B-movie throwbacks, I would argue the film’s politics are intentionally muddied and rough around the edges. That perspective is no more transgressive than the onslaught of earlier slasher films that had similar narratives about white teenagers during that subgenre’s many ups and downs. Without getting into spoilers, several characters are transformed due to their experiences with Temptress, yet their evolution isn’t necessarily a result of their immorality with her or their acceptance of archaic ideations. What’s here is an entertaining if under-discussed effort that is flush with style (in large part due to cinematographer and Spike Lee collaborator Ernest Dickerson), provocative substance, and a campy tone that would be replicated by Dickerson’s Bones (2001) a decade later and seldom again after that.

Vampires vs. the Bronx

Where to watch: Netflix

In the next 30 years after Def by Temptation, Black vampire films like Vampire in Brooklyn, Queen of the Damned, and Spike Lee’s Ganja & Hess remake Da Sweet Blood of Jesus would arrive with little fanfare. However, Oz Rodriguez’s Vampires vs. the Bronx provides a different tackling of racial issues in the modern era through the guise of gentrification, while also being a rare attempt at kid-friendly horror. This vampire horror comedy follows a group of teenagers that take up the fight against white vampire invaders who have begun buying up and pushing out local businesses to make way for their new nest. On its face, the allegory of the film is obvious: certain neighborhoods and cultures are pushed aside for white comfort. However, instead of allowing those inhabitants who chose to give up their businesses and livelihoods for a lump sum of money to have a better life, in Rodriguez’s film, they are killed off. To lose their culture and history while simultaneously being denied both comfort and existence from this arrangement is just a thumb in the eye. The film is geared more toward a kid-friendly audience for sure, but what makes it stand out so much is its willingness to be upfront about its social issues in both big and subtle ways while being an entertaining horror movie that still maintains a deft balance of tone that is approachable for all ages.

The film is in touch with its monster movie roots, as well. Blade is the first and most obvious nod, as the young trio reference the film constantly and even sneak away to rewatch it at one point to get a refresher on vampire lore. And in what should be a new generation’s The Monster Squad, given its family-centric tone, Rodriguez also finds time to sneak in cheeky nods to the vampire lore of old. The real estate agency “Murnau Properties” is a reference to the famous occult director of the original Nosferatu, and the character of Polidori (Shea Whigham) is a nod to John William Polidori, the creator of the first published modern vampire story, the 1819 short story “The Vampyre.” All of this charm comes in at a brisk 86 minutes that serves as a rare piece of fun gateway horror for the whole family, with authentically lived-in characters and unapologetic representation of the multiculturalism at the heart of the Bronx.

The Last Voyage of the Demeter

Where to watch: Paramount Plus w/ Showtime, or for digital rental/purchase on Amazon, Apple TV, Fandango at Home

The past few years saw the arrival of Black as Night, Day Shift, The Invitation (2022), and most recently André Øvredal’s The Last Voyage of the Demeter, an adaptation of the chapter “The Captain’s Log” from Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Directly inspired by Ridley Scott’s Alien, Øvredal’s film follows the doomed crew of the Demeter as they contend with a vampiric stowaway en route to England. But where Scott’s film dealt with issues of class and the expendable nature of a blue-collar crew in the face of unrestrained capitalism, Demeter deals more directly with issues pertaining to race and gender.

These issues are linked to the two marginalized characters on board, Clemens (Corey Hawkins) and Anna (Aisling Franciosi), who find themselves at the mercy of racist and gendered superstitions, respectively. Clemens is a graduate from Cambridge who traveled to Varna to become a doctor for the local royalty, only to be rejected due to the color of his skin. These racial tensions follow him onto the doomed Demeter, where many of the crew look at him sideways. Anna, on the other hand, is subjected to the sailor superstition that women are bad luck on a seafaring vessel, and is threatened several times with being thrown overboard when tensions rise. By the finale, both characters are able to exert some manner of control over their own realities.

On top of some excellent creature design that showcases a winged Nosferatu-like monster that is seldom seen across Dracula adaptations, the overall set design of the Demeter and violence on display harken back to the Hammer horror of old, with its ominous darkened passageways and mangled leftover bodies. Øvredal complements the grim atmosphere with his signature mean streak that can be found in Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark and The Autopsy of Jane Doe, truly giving a sense that anyone could die. This viciousness allows Øvredal a certain freedom to add his own wrinkles and characters to the narrative, even with a preset beginning and end from the source material. The film’s ending sets up a sequel for a fascinating remix of the original novel that could have seen a surviving Clemens hunt down the Prince of Darkness. While we may never see this idea come to fruition due to the film — like its namesake — sadly sinking at the box office, The Last Voyage of the Demeter is well worth a look.

Sinners

Where to watch: Now playing in theaters

Finally, we reach the movie that inspired this piece: Ryan Coogler’s Sinners. The film follows the SmokeStack twins (Michael B. Jordan), veterans and former gang members who return to their hometown to open a small juke joint. Headlining the music of their new establishment is their cousin Sammie (Miles Caton), a burgeoning blues player whose talent has the ability to conjure spirits from the past and future, as well as summoning the vampire menace that threatens them all. What follows is an engrossing tale that has enraptured me in a way I have not felt since Jordan Peele’s monumental Nope. Even with the usual musings of race, identity, and masculinity on the director’s mind, what struck me most is his reverence for genre fare like From Dusk Till Dawn and The Thing. It is all of those things, and yet still his, and by extension, ours. Coogler establishes a world full of possibility and lived-in authenticity, yet his focus on this single day enriches a narrative that oscillates between love, tragedy, and the fantastic bloody violence that caps off the evening’s festivities.

Music plays a prominent role in Sinners, one that connects its characters — good and evil alike — to their ancestry and shared history of oppression and assimilation. But it also connects Sinners to previous entries in the Black vampire cinema canon. The film has a musical connection to Ganja & Hess with the Clipping song “Blood of the Fang.” The opening of the song uses lyrics from Sam Waymon’s “The Blood of Thing (Part 2) Shadow of the Cross,” which appeared at the beginning of Ganja & Hess, and the beat that precedes these lyrics in Waymon’s version was used for Sinners’ first trailer. Coogler uses the Delta blues to chart the history of Black and African American society that bonds centuries of culture together, showing both his attention to detail and his knowledge of the cinematic tradition he is working in. In one incredible scene, Sammie plays his music so powerfully that it conjures spirits from the past and future to play alongside him. From tribal players to ’80s guitarists to modern-day DJs, the dance floor is packed with those who were and those that will be, to fill a room with a culture that is unequivocally Black.

The main villain in the story is Remmick (Jack O’Connell), whose honeyed words promise salvation for the patrons of the juke joint but are a ruse for him to take Sammie’s talent and power for his own. With this villain, Coogler posits the idea of white vampires as culture vultures who want to absorb the talents of Black people without the voices of those people who cultivate it. Yet Coogler also contributes a new layer of meaning to this villain. In Sinners, vampires aren’t necessarily just white invaders that seek to prey on Black people and their culture. Instead, vampirism is treated like a disease that is spread from one colonized group to another. Remmick exemplifies this idea as an Irish immigrant forced to assimilate into imperial British culture centuries ago. As a vampire, he now — unwittingly or not — furthers the goals of his own oppressors that control societal systems. Remmick spreads his infectious assimilation to further homogenize a community already barely eking out an existence in the Mississippi Delta.

Ultimately, Sinners’ place within the Black vampire pantheon is one that vividly pleads the need for spaces that incorporate not just Black ownership and creativity in arenas owned by oppressors, but multicultural voices that thrive together, free to express and chart their own paths from the chains of centuries of passed-down assimilation. Where Sinners is unique is in its usage of the Delta blues and Irish folk music to speak on the ideas of cultural assimilation, not just to connect the oppressed to their past and future, but also in how that music is carried within a people for generations to come — a symbol of their perseverance and evolution.

As a whole, the Black vampire subgenre is one that has a multifaceted depiction of the monster. On one hand, they could be gentrifiers and silver-tongued devils meant to persuade the innocent into letting their guard down before terror strikes. On the other, they could be a long-forgotten tradition meant to be embraced in the face of white homogeneity. But as proven by Sinners, the vampire — like most monsters that embody the “other” — will continue to be a resonant metaphor for the problems of yesterday and today, and we must be vigilant about letting the right one in.

Source:https://www.polygon.com/horror/562913/sinners-black-vampire-movies-list-watch